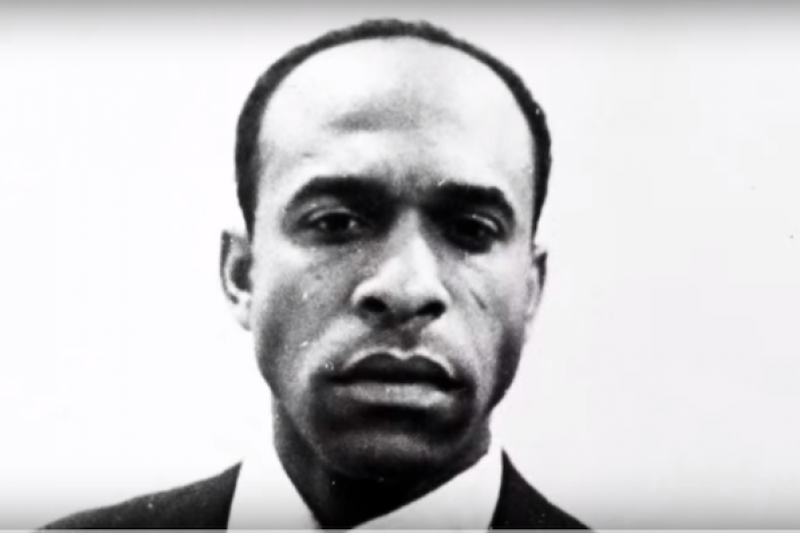

Frantz Omar Fanon is also known as Ibrahim Frantz Fanon. He was a French West Indian psychiatrist and political philosopher from the Martinique French colony. Frantz Fanon’s works have become influential in critical theory, Marxism, and post-colonial studies. Apart from Fanon being an intellectual, he was a Pan-Africanist, political radical, and Marxist humanist concerned with colonization psychopathology and the social, human and cultural consequences of decolonization.

In his work as a psychiatrist and physician, Frantz Fanon supported Algeria’s War of Independence from France and was an Algerian National Liberation Front member. For over 50 years, the life and works of Fanon have inspired national-liberation movements and other radical political organizations in Sri Lanka, SA, Palestine, and the US. Fanon formulated a community psychology model, believing that mental-health patients would do better if they got integrated into their community and family instead of receiving institutionalized care. Frantz Fanon aided in establishing the institutional psychotherapy field while working at St. Alban under Francois Tosquelles and Jean Oury.

Frantz Fanon published several books, including ‘The Wretched of the Earth.’ This work concentrates on what Fanon believed is the necessary role of violence by activists in decolonizing struggles.

His Early Life

Frantz was born on the Caribbean Island of Martinique. Felix Casimir Fanon, his father, was a descendant of African slaves and worked as a customs agent. Eleanore Medelice, his mum, was of white Alsatian and Afro-Martinican descent and worked as a shopkeeper. Frantz Fanon was the third of four sons in a family of more than seven children. Two of them lost their lives while young, including Gabrielle, his sister. Fanon’s family was socio-economically middle-class. His family could afford the fees for the Lycee Schoelcher, where Frantz came to admire one of the school’s teachers, writer, and poet Aime Cesaire. Frantz left Martinique in the mid-20th century (1943) when he was eighteen years old to join the Free French forces.

Martinique and WW 2

After the French power fell to the Nazis in 1940, Vichy French naval soldiers got blocked on Martinique. Forced to remain on the Island, French sailors took over the Martiniquan people’s authority and formed a collaborationist Vichy regime. In the face of economic distress and seclusion under the blockade, they established an oppressive government. Frantz Fanon described them as taking off their masks and acting like real racists. Residents made several complaints of sexual misconduct and harassment by the sailors. The French Navy’s abuse of the Martiniquan people influenced Frantz Fanon, reinforcing his alienation feelings and his disgust with colonial racism.

After Fanon left Martinique to join the French forces, he enlisted in the Free French Military and joined an Allied convoy that reached Casablanca. Later, he went to an army base at Bejaia on the Kabylie coast of Algeria. Frantz Fanon left Algeria from Oran and served in France in the battles of Alsace. In 1944, he got injured at Colmar and got the Croix de guerre. When the Nazis got defeated, and Allied forces crossed the Rhine into Germany along with photojournalists. Frantz regiment got bleached of all non-white soldiers. Frantz and his Afro-Caribbean soldiers went to Toulon. Later, they went to Normandy to await repatriation.

During the War, Frantz got exposed to white European racism. In 1945, Frantz returned to Martinique. He lasted a short while there. Fanon worked for the parliamentary campaign of Aime Cesaire. Aime ran on the communist ticket as a parliamentary delegate from Martinique to the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. Frantz stayed to finish his baccalaureate and went to France, where he studied psychiatry and medicine. After qualifying as a psychiatrist in 1951, Frantz did a residency in psychiatry at Saint Alban-Sur-Limagnole.

MORE:

- Biography of Adebayo Ogunlesi: A Nigerian Business Mogul

- The Biography of Kumi Naidoo: A South African Activist

Fanon in Algeria

After his residency, Frantz Fanon practiced psychiatry at Pontorson, near Mont St. Michel, for another year and then in Algeria. Fanon was chef de service at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. Frantz worked there until his deportation in 1957.

Frantz’s treatment methods started evolving, particularly beginning socio-therapy to link with his patients’ cultural backgrounds. Fanon also trained interns and nurses. Following the Algerian Revolution outbreak in the mid-20th century, Frantz Fanon joined the Front de Liberation Nationale after contacting Dr. Pierre Chaulet in 1955.

Working at a French hospital in Algeria, Frantz became accountable for treating the psychological distress of the French officers and soldiers who carried out torture to suppress anti-colonial resistance. Besides, Frantz was also accountable for treating Algerian torture victims.

Frantz Fanon made extensive trips across the Algerian state to study the psychological and cultural life of Algerians. Fanon’s lost study of the ‘The marabout of Si Slimane’ is an example. These trips were also a means for secretive activities.

Joining the FLN and Exile from Algeria

By 1956 Frantz Fanon realized that he could no longer continue to back up French efforts, even indirectly through his hospital work. In November that year, Fanon submitted his letter of resignation to the Resident Minister.

Afterward, Frantz got expelled from Algeria and shifted to Tunis, where he joined the FLN. Fanon was part of the editorial collective of El Moudjahid, for which he wrote until his demise. He also served as Ambassador to the Ghanaian state for the GPRA (Provisional Algerian Government). Frantz attended conferences in Conakry, Accra, Addis Ababa, Cairo, Leopoldville and Tripoli. Many of his shorter works from this time got collected posthumously in the book ‘Toward the African Revolution.’ In this work, Frantz Fanon reveals tactical war strategies.

Upon his return to Tunis, after his tiring trip across the Sahara region to open a Third Front, Frantz Fanon got diagnosed with Leukemia. Fanon went to the Soviet Union for treatment and experienced remission of his illness.

The Death of Fanon and the Aftermath

In 1961, the CIA arranged a trip to the United States for further Leukemia treatment at a National Institutes of Health facility. During his time in the US, Oliver Iselin, a CIA agent, handled Frantz Fanon. Frantz Fanon died in Bethesda on 6th December 1961, under the name of Ibrahim Fanon. His people buried him in Algeria after lying in state in Tunisia. Later on, people moved his body to a martyrs’ graveyard at Ain Kerma in Eastern Algeria. Josie, Fanon’s French wife, Olivier Fanon, their son, and Fanon’s daughter from a previous relationship survived Frantz Fanon.

Later, Josie died by committing suicide in Algiers in the late 20th century (1989). Mireille became a professor at Paris Descartes University and a visiting professor at the University of California in conflict resolution and international law. She has also worked for the French National Assembly, UNESCO and serves as President of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. Olivier Fanon worked through to his retirement as an official at the Algerian Embassy in Paris. He became Head of the Frantz-Fanon National Association, which came into existence in Algiers in 2012.

The Legacy of Frantz Fanon

Frantz Fanon has influenced national liberation movements and anti-colonial. In particular, Les damnes de la Terre was a significant influence on the work of revolutionary leaders such as Ali Shariati, Steve Biko, Malcolm X, and Ernesto Che Guevara. Guevara was mainly concerned with Frantz’s theories on violence. For Shariati and Biko, their interest in Frantz Fanon was the new man and black consciousness.

About the American liberation struggle called The Black Power Movement, Frantz’s work was particularly influential. Fanon’s book ‘Wretched of the Earth’ is quoted directly in Stokely Carmichael’s preface and Charles Hamilton’s book. Besides, Hamilton and Carmichael include much of Frantz’s theory on Colonialism in their work, starting by framing the situation of former slaves in America as a colony located within a nation.

The Black Power group that Frantz had the most influence on was the BPP. In 1970, Bobby Seale published a collection of recorded observations made while he got incarcerated entitled ‘Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton.’ This book is a primary source chronicling the BPP’s history via one of its founder’s eyes. While describing one of his first meetings with Huey Newton, Bobby Seale describes bringing him a copy of ‘Wretched of the Earth.’ There are at least 3 direct references to the book, all of them mentioning how the piece was influential and how it got added to the curriculum required of all new BPP participants.

Beyond reading the text, the BPP and Seale included much of the work in their party platform. The Panther 10 Point Plan had six points that either indirectly or directly referenced Frantz’s work ideas, including their contention.

Fausto Reinaga had some Frantz influence, and he mentions The Wretched of the Earth in his magnum opus La Revolucion India. Frantz’s influence extended to the liberation movements of the Tamils, the Palestinians, and African Americans. Frantz affected modern African literature. His works serve as a vital theoretical gloss for writers.

Frantz Fanon’s legacy has increased even further into Black Studies and, more specifically, into Black Critical Theory and Afro-pessimism theories. Thinkers such as Sylvia Wynter, Frank Wilderson 3, David Marriott, Jared Sexton, Patrice Douglass, Axelle Karera, and Selamawit Terrefe have taken up Frantz’s phenomenological, ontological, and psychoanalytic analyses of the Negro and the zone of non-being to develop theories of anti-Blackness.