The Dinka are a community of several closely connected people who live on both sides of the White Nile in Southern Sudan. They are one of the world’s blackest and oldest inhabitants. Dinka founded the old Nubian kingdom with other tribes in Sudan. The Dinka is one of the tallest people globally, much like the other tribes like Nuer, Turkana, Samburu, and Masai. The average height for males is 1.9 m (6 feet, 4in), while females are 1.8 m (6 ft). These individuals have slender yet solid bodies, and their heads are longer than the average African Black.

The first people created by God (Nhialic) were Garang and Abuk, now understood as the counterpart of Adam and Eve, according to an ancient theory preserved in several parts of Dinka. Deng was the firstborn to whom all Dinka people descended.

Identity: Dinka is one of the branches of River Lake Nilotes. While they have identified themselves as Dinka for millennia, they refer to themselves as Jieng (Upper Nile) or Muonyjang (Bahr el Ghazal) as “people of the people.” The Nuer call them “Jiang;” they are known as “Jango,” and the Arabs and Equatorians term them Jiengge; they are both Jiengs. The Dinka is South Sudan’s main single national grouping. Numbering about 2.5 to 3 million and including more than 25 Dinka segment aggregates (Wut). The more diverse branches of southern Luo are located in central Uganda and neighboring parts of Zaire and western Kenya. The populations of Dinka continue to remain near the hot and humid homeland of River-Lake Nilotes. They are South Sudan’s largest ethnic group. The Dinka group maintains the typical pastoral life of the Nilotes, but in some regions have introduced farming, cultivating rice, peanuts, beans, maize, and other crops. Women are mostly farmers, but men clear forests for their gardening site. Two plantings normally occur each year. Some are fishermen. Their culture includes strategies for the regular dry season and lengthy rainy season cycle.

Dinka language (thong muonyjang or thong-jieng) is spoken in its various varieties (dialects). It is not shocking if certain pieces are incomprehensible to others due to this variety. Tonj’s Rek is said to be Dinka’s standard language. The Dinka language covers the other Nilotic language community.

Before the British came, the Dinka did not remain in settlements but moved to family communities with their cattle in temporary homes. The properties could have up to 100 families in groups of one or two. Around the British administrative centers, small villages rose. A community leader heads each community of an extended family.

Traditional houses were composed of mud walls and conical roofs that could survive for about 20 years. The women and men slept in the house while the men sleep in a mud-roofed cattle pen. The properties were located to encourage travel throughout a range that allowed access to grass and water the entire year. Permanent villages are constructed on the higher ground over the Nile flood plain but ensure they have good water for irrigation. Women and older men remain and tend to crops on the higher grounds while younger men travel up and down with the rising and falling river.

Marriage is compulsory among the Dinka. Polygamy among Dinka is permitted, although many men might have one wife only. The Dinka should be married outside their clan (exogamy), which encourages further harmony within the wider Dinka community. Relatives marry the fantasy of a man who died in childhood – these practices have brought several ‘ghost fathers’ among the Dinka.

The bride’s family is paid a “bridewealth” to finalize the marriage alliance between the two clan families. Levirate marriage offers widows and children protection. All children of co-wives have a wide family identity. Co-wives cook for all children, even though every wife has a duty for their children.

The daughters of Chief fetch more livestock in the same fashion as Chief’s son, his wife, is required to pay more livestock. University graduates pick up different wedding rates, which is expected to impact girls’ enrolment in colleges. Like other Nilotic groups, Dinka sex is for social reproduction only. Fornication is thus prohibited; adulterers are hated and harshly punished, which is often a cause of dispute and clan struggle. Incest is typically unimaginable and disgusted.

Each man of Dinka receives an ox from his parent, uncle, or the person responsible. His ‘bull-name’ can be derived from the color of a girl and her cattle (Ayen, Yar, etc.) or a child (Mayom, Mayen, Malith, etc.) as well as other Dinka titles, from the color of the father’s best ox (mayom, malith, mayan) or cow (ayen, yar). Like other Nilotic groups, the Dinka have particular names for twins: Ngor, Chan, Bol, etc.

The Dinka have a great vocabulary for livestock, their colors and take great interest and pleasure in the art of creating various conformations for which their horns can cultivate. When talking about something or dancing, a Dinka normally throws his arms in imitation of the form of ox’s horns.

Initiation represents the transition from boyhood to maturity for a young man. An initiate is referred to as a parapuol, “One who stopped milking.” Initiation implies he no longer does the milking, tying the cattle and carting dung work mostly done by boys. Mutilation – tribal markings with many parallel lines or V-shaped marks – are marked by initiation on the youth’s forehead.

The pattern of the scars will vary with time, but the parapuol is still quickly recognized as part of a certain tribe. This scarification occurs at every age from 10 to 16. Initiates are hunters, camp guards against animals – tigers, hyenas – and enemy raiders. Some remain with the cattle during the year. They all remain with the livestock throughout the dry months, but most of them go back to the villages to support the crops grow during the rainy season. The parapuol has the position of guerrilla protectors, even in this duty. The livestock, covered by the parapuol that stay with them, are held for the whole wet season in camps on the plains at the base of the foothills.

Initiation takes place during the time of harvest. The night before the ritual, the boys gather to perform their clans’ songs. In preparation for the initiation ceremony, their heads had already been shaved. At dawn, their parents are picked and brought to the location of the ritual. Since getting a blessing, the boys get back in line and sit cross-legged behind the rising sun. As the initiator returns to each child, he calls his ancestors’ names. The initiator ties the head of the boy closely to the blade of a very sharp knife. After the first slash, the initiator then renders the second and third etc., regardless of the sequence of the clan of scars. The wounds are profound; indeed, skulls have been found that have clear marks on the bony forehead. Psyched from a night of clan singing, the initiate stares straight ahead and always recites his ancestors’ names.

This is the moment he waited; when he joined the ranks of the warriors and set aside the poor boyhood position and the dissatisfaction tasks he serves, he assumed the status of guerrilla with all the rights and honored this entails. He is declared to be a hero and a citizen by his initiation scars and therefore courageous and proud. Flinching or yelling during the rite of initiation will mean denying its bravery and thereby disgracing its families and ancestors. A kink in his initiation scars would make him a coward who would be obvious to everyone.

If all initiates were scarred ritually, their fathers clean the blood from the eyes and mouths of their sons and wrap a wide leaf across their foreheads. Initiation scars suggest a man will marry — parapuols can start courting deserving ladies. The boys are given a knife, a club, and a shield – appropriate warrior accouterments. There is much joy in the band for a few days of music and dancing. Following his initiation, a parapuol is granted oxen, its “song oxen.” He is his most prized asset and can carefully practice his horns in extraordinary, frequently asymmetrical shapes.

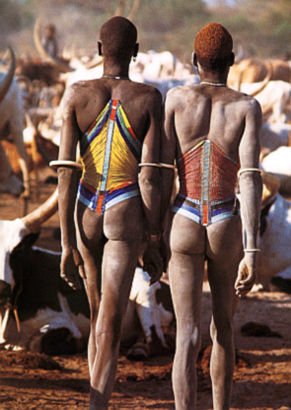

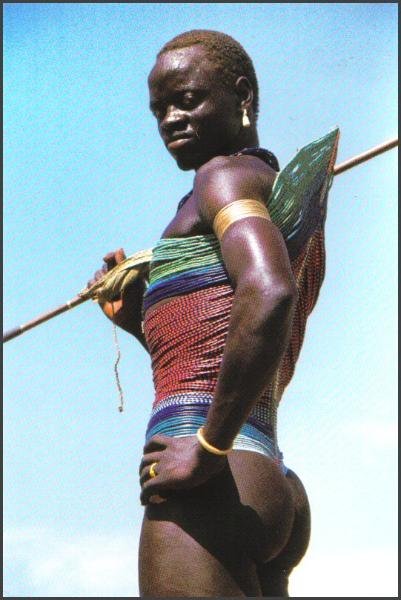

Girls learn how to cook while boys do not. Outdoor cooking is performed in pots on a hot stone. Men rely on women in many ways, but the division of labor often assigns such duties for men, such as fishing, herding, and regular hunting. Since maturity, the social realms of the sexes have rarely differed. The important meal is a thick porridge of the millet, eaten with milk or vegetable sauce and seasoning. Milk itself is also the main food in different ways. The Dinka wear little clothes, especially in their village. Adult males sport the so-called “malual” corset. It reveals all areas of the body except beads around the neck or wrist. The women usually only wear goatskin dresses, but unmarried young girls are usually naked. These garments are used to convey gender, age, income, or ethnic affiliation characteristics.

“The tight beaded corsets indicate the men’s position in the age-set system of the tribe. The corsets are first sewn in place at puberty and not removed until the wearer reaches a new age set. Each group wears a color-coded corset: a red and blue corset indicates a man between fifteen and twenty-five years of age; a yellow and blue one marks someone over thirty and ready for marriage.”

“In the mid-1990s, the Dinka beaded vest and corset, collected in Southern Sudan, were shown in “Beads of Life.” This style of ornament was first brought to the general public’s attention with Angela Fisher’s Africa Adorned (1984), which immediately turned the citizens of Dinka into an exotic attraction at the time of the South Sudanese War. Although only worn by Dinka Bor, they have gained emblematic status among some of the Dinka war refugees who produce woolen corset versions and often dance while wearing them.

These ornaments possibly occurred in the second half of the 20th century, when glass beads became more widely accessible in Southern Sudan. They are “extensions” to already established men’s belts and women’s necklaces. The male corset is readily identified by its “horn” (fungi), which lies behind the body towards the sky. Cowrie (gak) shells are sewn at the front and rear of the female west, presumably to safeguard the wearer’s fertility. Both corset and vest come in various colors, each connected to a certain age category. In her early twenties, a male would have worn the corset, and in her late twenties, a married woman would have worn the vest.”

The close beaded corsets show the role of the men in the tribe’s age-set structure. The corsets are sewn at puberty first and are not replaced before the owner hits a new age. Each group has a color-coded corset, with a red and blue corset showing a man aged between 15 and 25; a yellow and blue mark someone over thirty and ready for marriage.

Clothes are getting more widespread. Some men can be seen in the long Muslim robe or the short robe. They have very few material properties of any sort. Personal care and decoration are appreciated. The Dinka rub their bodies with hot butter oil. Decorative patterns are carved into the flesh. They cut some teeth to repel mosquitoes and wear dung ash. Men thin their hair red with cow’s pee, while women shave their hair and eyebrows but leave a hair knot on top of their head.

The Dinka are an acephalous ethnicity – a federation with ethnic sub-nationalities rather than political ones. Among Dinka, there is no idea of State and therefore government structures, organization, and hence authority. Each part of Dinka is itself an independent political body. Formerly “chief of the fishing spear” or “spear masters” had the main impact. This elite community supplied health with magical strength. Chieftainship is hereditary and bears the rank of beny, which means many items, such as leader, specialist, or military officer. The title often has an attribute, such as beny de ring or beny rein (or riem) — northern Dinka and beny Bith in the rest of the world. The term ring (or rem) presumably refers to the Chief’s spiritual influence. On the other side, bith is the holy fishing spear as a sign of office (a non-barbed or non-serrated spear). Spiritual leaders (fishing spearhead, women, and Deng’s chiefs in medicine) are very influential. Spiritual figures oppose secular power more frequently than not, except in some instances. Through persuasion, Dinka’s chiefs did not use any established weapons of coercion and aggression. Their position was eradicated because of changes caused by British rule and the modern world. Their society is equal, without a hierarchy of classes. All, rich or poor, should contribute to the greater good.

Poetry and music are the main modes of art. There are several kinds of songs for various life events, such as festivals, fieldwork, war preparedness, and ceremonies. Songs teach history and collective identity and retain it. They sing their ancestors and the living love songs. Songs are also used in competition ritually to settle a legal dispute. Women are still producing pottery and weaving baskets and mats. Men are blacksmiths who produce all kinds of tools.

The Dinka lifestyle focuses on their livestock: the positions of people in their communities, their beliefs, and their practices all represent this. The cattle have milk (butter and ghee), urine for cleaning, hair coloring, and tanning hides. Dung fuels fires from which ash is used to hold the livestock safe and clear of blood-sucking ticks, to decorate the Dinka (body art) itself, and to paste the teeth to smooth. Although the cattle are not slaughtered for feed, meat is consumed, and the hide healed if one dies or is sacrificed. For mats and drum skins, pads, skins, cords, and hangers are often used. Horns and bones are used for a variety of functional and esthetic items.

Modernity and foreign ideas also permeated Dinka society and replaced its beliefs and rituals steadily. They followed either jellabia or European clothing, and today, in the cattle camps, nudity and skin wearing are seldom seen.

Religion: The Dinkas believe in a single universal God, called Nhialac. They believe that Nhialac is the maker and root of creation, albeit far from human relations. Human beings touch Nhialac through divine intermediaries and so-called yath and jak powers, manipulated with different rituals. Healers and diviners control these practices. They claim that the dead souls are part of the divine realm of this world. They refused to convert them to Islam, but they were very receptive to Christian missionaries. Cattle have religious importance. They are the first option as a sacrificial cow, while sheep may be sacrificed sometimes as a replacement. Yath and jak could be sacrificed, as Nhialac is too far away for direct human touch.

Recent Developments

The Dinka were impacted by fighting, as were other nationalities in South Sudan. Many were homeless and lived in neighboring countries either as internally displaced persons (IDPs) or refugees. This has influenced the societal structure, customs, and attitudes. Dinka has interacted with the war in Bahr el Ghazal, and its demands have led to the usage of their cherished livestock in agricultural production.

Many merchants have traveled to Uganda and the Congo hundreds of kilometers to sell their bulls and return consumer products. International assistance and humanitarian aid inputs; the economic monetization and transportation motorization progressively but gradually leads to progress in the lives of the Dinka.

In Europe, America (Lost Boys), and Australia, the war formed a Dinka Diaspora. Some diaspora retains close connections and contact with their family member’s home; they regularly send money to help them.

DinkaRead More: The Mandinka Ethnic Group

The Dinka Tribe Spear Masters

According to mythology, the Spear Masters of the Dinka Tribe of the Upper Nile are hereditary priests who are enhanced by political and theological beliefs. According to mythology, the Spear Masters of the Dinka tribe of the Upper Nile are hereditary priesthood and are reinforced by political and theological beliefs.

There are many stories about the source of this spear, one of which has a lion and a man dancing. The lion needs a bracelet which the man wears and declines to remove. In exchange, the lion bites off his thumb to assert his belief, and he dies during the fight. The man leaves a woman and a girl without a son behind. The daughter screams on the river, and the spirits ask her why she is yelling. She says that she has no son, and the river asks her to raise her skirt to feel the waves blow up against her womb. “A spear is given to her, a sign depicting a male infant, a fish to eat, and he is ordered to return home.” Aiwel, a male infant with complete teeth, is able to be born into the woman, a symbol of sacred authority.

As an infant, Aiwel is skillful and uncomfortable, performing tricks when his mother is away. For one case, the mother returns, and all the milk is gone. She accuses her daughter instantly, who feverishly rejects the allegation. The mother feels like hiding in her house, and to her delight, Aiwel gets up and goes to the gourds of milk and drinks. She runs into the room and sees plainly that Aiwel steals the milk. She tries to accuse him of the act, but he said she’d die if she told anyone. She didn’t keep the secret, and she died just as expected. Aiwel was vibrant with the strength of the spear master when he used the power of language to realize everything.

Aiwel couldn’t survive with his family anymore, so he traveled to the river where he and his spiritual father grew up. When he became a child, with an ox of several colors named Longar, he returned to the village. He brought up cattle and worked his ranch. A famine arrived, and the villagers had to find other ways of surviving, bringing their bovine animals to lands abundant in grass and water. However, their cattle continued to die while the cattle of Aiwel continued to thrive and rise.

However, their cattle continued to die while the cattle of Aiwel continued to thrive and rise. The village’s young men spied on him, eager to find out what Aiwel was doing to keep his herd safe. Aiwel learned this, and all of them died when the men warned everyone of the code. Aiwel tried to encourage the people, even convincing the elders to abandon their lands and bring them to the promised land. They resisted, as Aiwel suspected, and he saw the villagers behind him as he was on his journey. He created barriers in their way when the others were even standing on the other side of a canal. He used his blade to attack all the men he attempted to cross. A man named Agothyathik saw something and wanted to schedule a detour. Aiwel tried to puncture it with his spear when a villager carried a bone big enough to form a human skull.

Simultaneously, Agothyathik came, and they battled until Aiwel was exhausted and gave up. While they stayed very afraid, he told people to come over and offered them war spears and fishing spells. The men who crossed were organized into a clan named the masters of the spear. The men who followed were a war spear masters clan. They were left to rule the region, but Aiwel would return if he needed help in trouble.