Often when questions pop up about the Kalanga, what comes to our mind is groups of diverse affiliated tribes. That’s because these groups were victims of invasion, colonized by the Ndebele, having to transit from their cultures. The Kalanga were once inhabitants of the same ancestry and language, occupying the Kalahari Desert land.

The Origin of the Kalanga

Kalanga or Karanga are the same people; however, Kalanga was the original word. Most scholars suggest that Karanga was a Portuguese word for Kalanga. During the 12th, 16th Century when the Portuguese came to Africa, they would refer to the Kalanga as Mocaranga. And that gave rise to the name Karanga.

History predates the Kalanga to have originally migrated from North East Africa, to be precise Sudan, Egypt, and the Ethiopian region. However, like many Bantus, they traveled in search of suitable farming lands, and it was long before they finally settled in the southern part of Africa. By the 100AD, they had occupied the lands we to date call Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Botswana.

In west Zimbabwe, the Kalanga were the Nambya, east, north Zimbabwe Nyai, south Zimbabwe and Botswana Batalaunda Zambia Rozvi. The native language for these Kalanga groups existed in two forms. There was the TjiKalanga or rather Kalanga in western Zimbabwe and Ikalanga in northeastern Botswana. Together with Nambya and the central Shona language, these varieties form a west branch of the group. Nevertheless, to date, the Kalanga’s have been reduced to mostly Ndebele speakers.

The States of the Kalanga People

By the 11th Century, the Kalanga people had established empires and states on the Zimbabwean plateau. The very first State was the Great Zimbabwe state, then Munhumutapa, Torwa, and then Rozvi.

The Great Zimbabwean State

It was an ancient city in the south-eastern hills of Zimbabwe next to Lake Mutirikwe and the town of Masvingo. Construction of the city kicked off in the 11th Century and continued until the 15th Century, when it was abandoned. The city buildings were believed to have been erected by Shona constructors. The city covered an area of approximately 7.22 square kilometers. Back then, such a place could accommodate up to 18000 people. UNESCO recognizes the ruins of the Great Zimbabwe State as a World Heritage site.

The Zimbabwe state used to serve as a royal palace for the local monarch. As such, it would occasionally host political meetings. One of the State’s most prominent features was its walls. They were eleven meters high yet constructed without dry stone. One of the greatest techniques to safeguard a Kingdom from enemies was establishing strong high walls during those days. Declines in lucrative coastal trade, overpopulation, overworking on land, and deforestation are some of the factors that might have promoted the collapse of the State in the 15th Century. The State has disintegrated into ruins, left to be studied as an archeological site and a national monument.

The Munhumutapa State

The Munhumutapa, Mutapa, Mwenemutapa are all names referring to the southern African State, located in the north of modern Zimbabwe along the Zambezi river. It flourished between mid 15th and 17th Centuries after succeeding the Zimbabwean State. Even though some people referred to it as an empire, there is little evidence to confirm that the Shona people established a kingdom in the region. The State prospered because it was rich in local resources such as gold and ivory. Often it exchanged goods with the Arabs on the coast of East Africa and the Portuguese during the 16th Century.

The Mutapa monarchs reigned overpopulations of warriors who were also farmers and herders. Occasionally the warriors fought against rival tribes and chiefdoms who eyed their wealth. The Mutapa Kingdom existed for about 500 years. Nevertheless, it collapsed around 1633CE because internal decay and external conflicts had weakened it.

MORE:

The Torwa State

The Tolwa or the Torwa also arose from the Great Zimbabwe State’s collapse around the 16th and the 17th Century. The Madabhale Shoko/Ncube was the group behind its establishment. Torwa dynasty of the Bakalanga based itself at the stone city of Khami from 1450 to 1683. The State prospered because of the cattle and gold trade.

While at Khami, they learned both stone building techniques and the pottery styles they found at Great Zimbabwe. Today, archeological reports reveal the discovery of several artifacts at Khami. Ritual drinking pots, iron, bronze weapons, and copper objects were some of the artifacts discovered. Also, artifacts from China and Europe remind of the excellent trade relations between the Asian, Portuguese, and the Kalangas at Khami.

The Torwa dynasty existed for 200 years before its downfall. Sources reveal that the State fell after being overthrown by Changamire Dombo / Dombolakona Dlembeu of the Rozvi empire. How did Changamire dethrone Torwa? Everything began with the arrival of the Mutapa people from the north and the Nguni intruders from the south.

In the 1679s, a new power arose in the Zimbabwean plateau led by a military leader called Changamire. He had a well-trained army, the Lozwi, who helped him overthrow the Tolwa dynasty. They drove away from the Portuguese from the Zimbabwean plateau in 1693 and then rose the Rozwi Empire, also known as Mambo.

The Rozvi State

The Rozwi, also known as Rozvi, was a former Kalanga empire in South Africa. Changamire was one of the most powerful rulers. He had conquered fertile, rich soils near the Zambezi River valleys after chasing away the Portuguese.

Amid the late 17th and early 18th Centuries, Rozvi State started experiencing challenges. Internal conflicts among smaller ruling dynasties started resulting in some chiefdoms breaking away from the Rozvi Empire. Constant attacks from BaMangwato and internal palace rebellions continued to steer political pressure on the Empire. Droughts between the 17th and the 18th Century in the region worsened the political tensions in the area.

During the same time, the demand for gold started declining; this significantly impacted the Shona tradition of gold mining. The trade that had lasted between them and the Portuguese for years had reduced. Their most significant trading partners had shifted their attention to the slave trade. It was not long before Rozvi’s power started to decline. And due to the multiple wars and invasions, the State became inferior and never recovered completely.

Successive attacks on the State by Mpanga, Ngwana, Maseko, and Zwangendaba were repelled, sending away the attackers. Nevertheless, tremendous damage had been done to the State. Without any time to recover, the Swazi queen Nyamazanana launched another attack, resulting in the capture of Rozvi’s capital and the murder of Mambo Chirisamhuru. However, that was not the end of Rozvi. More attacks preceded before finally, the Ndebele won.

MORE:

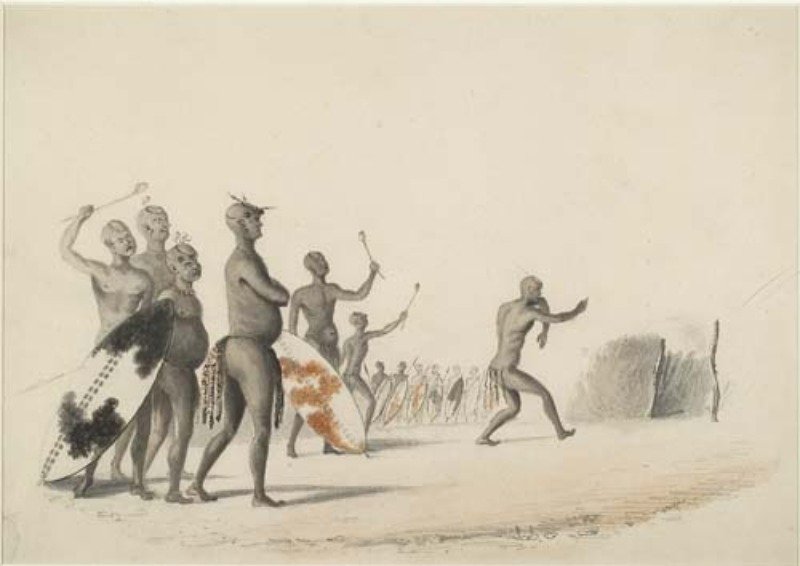

The Ndebele Invasion

Around 1839, the Ndebele invaded the Rozvi State. They had taken advantage of the declined power and weak army. When they successfully defeated the Rozvi, they completely alienated them from their culture, forcing most of them to adapt to their lifestyle. As such, the Kalanga from the west were cut from the majority of Shona in the east.

The Ndebele established a new state, which they named after their ethnicity. The Shona they had detained were forced to become part of Ndebele’s caste system, the amahole. Although a majority of the Shonas hated adapting to new cultures, some enjoyed the transition. As often, they would translate their totems from Shona to Ndebele. For instance, words like Shumbas in Shona were changed to Sibanda to Ndebele and Nyangas to Nkomo.

Captured boys were drafted to Ndebele amabutho and were made to undergo Ndebele boys’ rites of passage. Meanwhile, Shona women would grow into womanhood as other Ndebele females. Once women enough, they were married off to their stepfathers or by other men. Generally, embracing the changes was difficult at first; hence some Shonas rebelled.

A hundred years later, to be precise, in 1927, a Rhodesian missionary society arrived in the south, wanting to create a standard Shona orthography. Very made controversies arose on whether the Kalangas were of Shona dialect. Professor Clement Doke, a Bantu professor at the Witwatersranfmd University, was enlisted to research the Kalangas’. After thorough studies, Doke concluded that Kalanga could not be listed as part of the Shona dialect because their culture had been corrupt; they were phonologically diverse from Shona. Hence Professor Doke concluded that:

“The Kalanga group, though belonging to the Shona, has been strongly influenced by the north.”

The Kalangas’ having heard that, were displeased with both the Professor and the colonial government for failing to acknowledge their language. They were forced to remain within the official identity of the Ndebele.

To date, a lot has been said about the Kalangas’. Recently, President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe made disturbing remarks about the Kalanga. The controversial comment left many talking, and of course, some even labeled the President tribalistic. The remarks in question were made against the backdrop of unsubstantiated allegations that the terrific xenophobic attacks in South Africa were because governments in the region were allegedly pushing citizens into South Africa.

Mugabe’s comments of the Kalanga people as uneducated and notorious is not only in reference to Matabeland people but also to Zimbabweans at large.